To celebrate her role as wet-nurse of Horus and symbol of rebirth and resurrection in the celestial realm, this goddess is shown in the form of a cow emerging from the papyrus thicket ( 2007.155). In its ideal form, this was performed in the marshes by a celebrant who shook actual stalks of papyrus Hathor’s primary cult instruments, the sistrum ( 68.44) and the menat ( 11.215.450), were rattled to produce a comparable rustling sound and evoke this mythical environment. Horus was protected and nursed while a baby by the goddess Hathor, who was worshipped in the ritual of the Shaking of the Papyrus. Horus grew to manhood here, hidden among the swaying reeds whose rustling sounds soothed him and masked his cries, until he emerged to defeat his wicked uncle and reclaim his patrimony ( 50.85). In one of the great mythic cycles central to Egyptian religion, the goddess Isis took her infant son Horus to the papyrus thickets of the north to conceal him from her brother Seth, who had murdered her husband Osiris and usurped his throne. The single-handed defeat of these chaotic creatures by a king or noble, often depicted on the walls of temples and elite tombs, was emblematic of the maintenance of the ordered cosmos against the forces of entropy ( 30.4.48). Teeming with wild birds and fish as well as dangerous animals such as hippopotami and crocodiles, all seen as incarnations of Egypt’s enemies, these were the setting for ritual hunts. Papyrus thickets were seen as liminal zones at the edges of the ordered cosmos, symbols of the untamed chaos that surrounded and perpetually threatened the Egyptian world. Ceilings in temples and tombs were frequently supported with columns in the form of papyrus plants, turning their architectural settings into models of this primeval marsh ( 68.154).

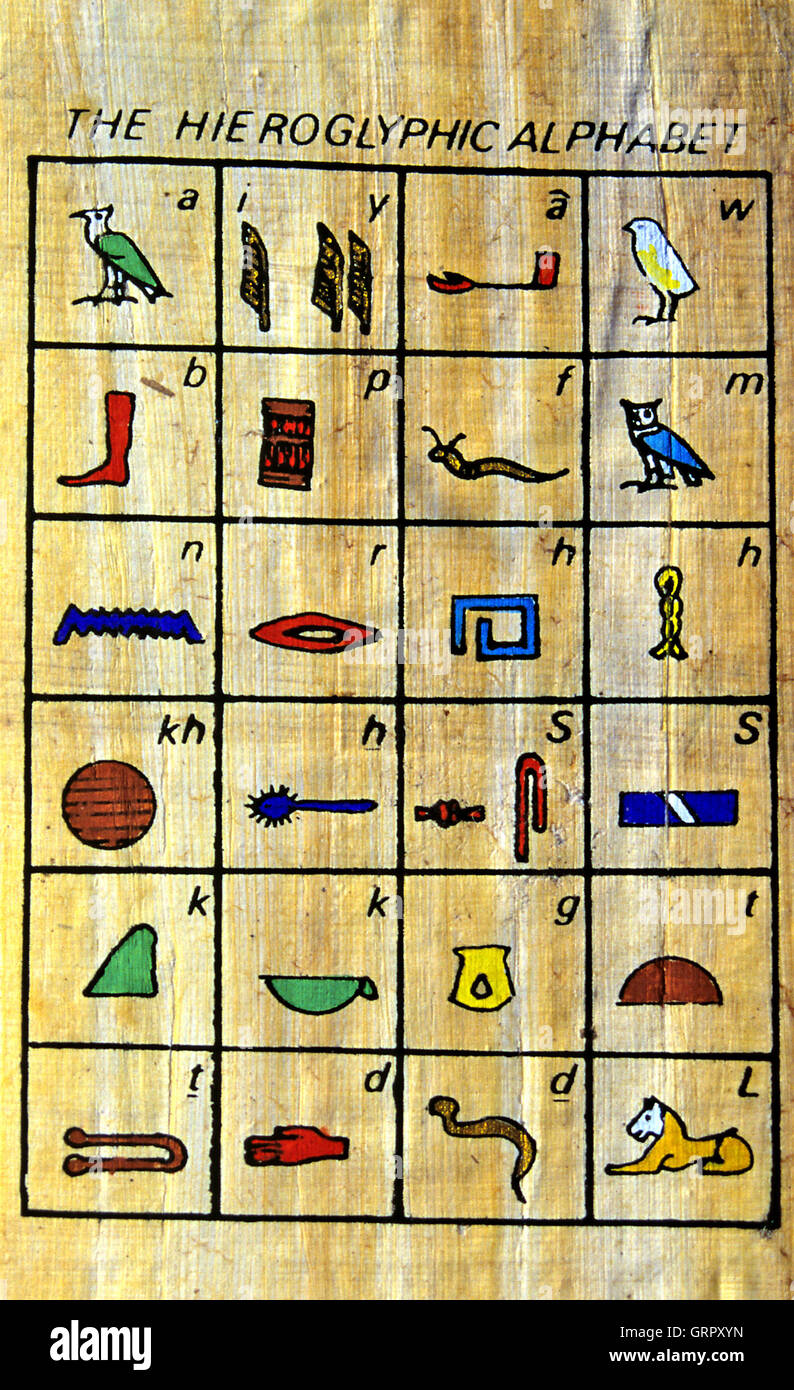

Papyrus marshes were thus seen as fecund, fertile regions that contained the germs of creation ( 30.4.136). In ancient Egyptian cosmology, the world was created when the first god stood on a mound that emerged from limitless and undifferentiated darkness and water, a mythical echo of the moment each year when the land began to reappear from beneath the annual floodwaters. The goddess Wadjet, depicted as a rearing cobra ( 07.228.14) or a woman with the head of a lioness ( 35.9.2), was the tutelary deity of Lower Egypt, and often is shown carrying a papyrus-shaped scepter. When shown wound around the hieroglyph for “unite,” these two plants formed an emblem for the unification of the Two Lands of Egypt ( 15.5.1). Due to its prevalence in the Nile Delta, the papyrus was the heraldic plant of Lower (northern) Egypt, while the lily or lotus stood for Upper (southern) Egypt. An amulet in this shape was worn at the throat for protection and health ( ). A hieroglyph in the form of a papyrus plant was used in the writing of the word wadj, meaning fresh, flourishing, and green. The pharaonic word for papyrus was tjufy (with mehyt used as a more general term for marsh plants). From a horizontal root, the slender but sturdy stalks, topped by feathery umbels ending in small brown fruit-bearing flowers, can reach up to five meters in height ( 30.4.60).

Needing shallow fresh water or water-saturated earth to grow, dense papyrus thickets were found in the marshes of the Nile Delta and also in the low-lying areas fringing the Nile valley. A member of the sedge family, the papyrus ( Cyperus papyrus) was an integral feature of the ancient Nilotic landscape, essential to the ancient Egyptians in both the practical and symbolic realms.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)